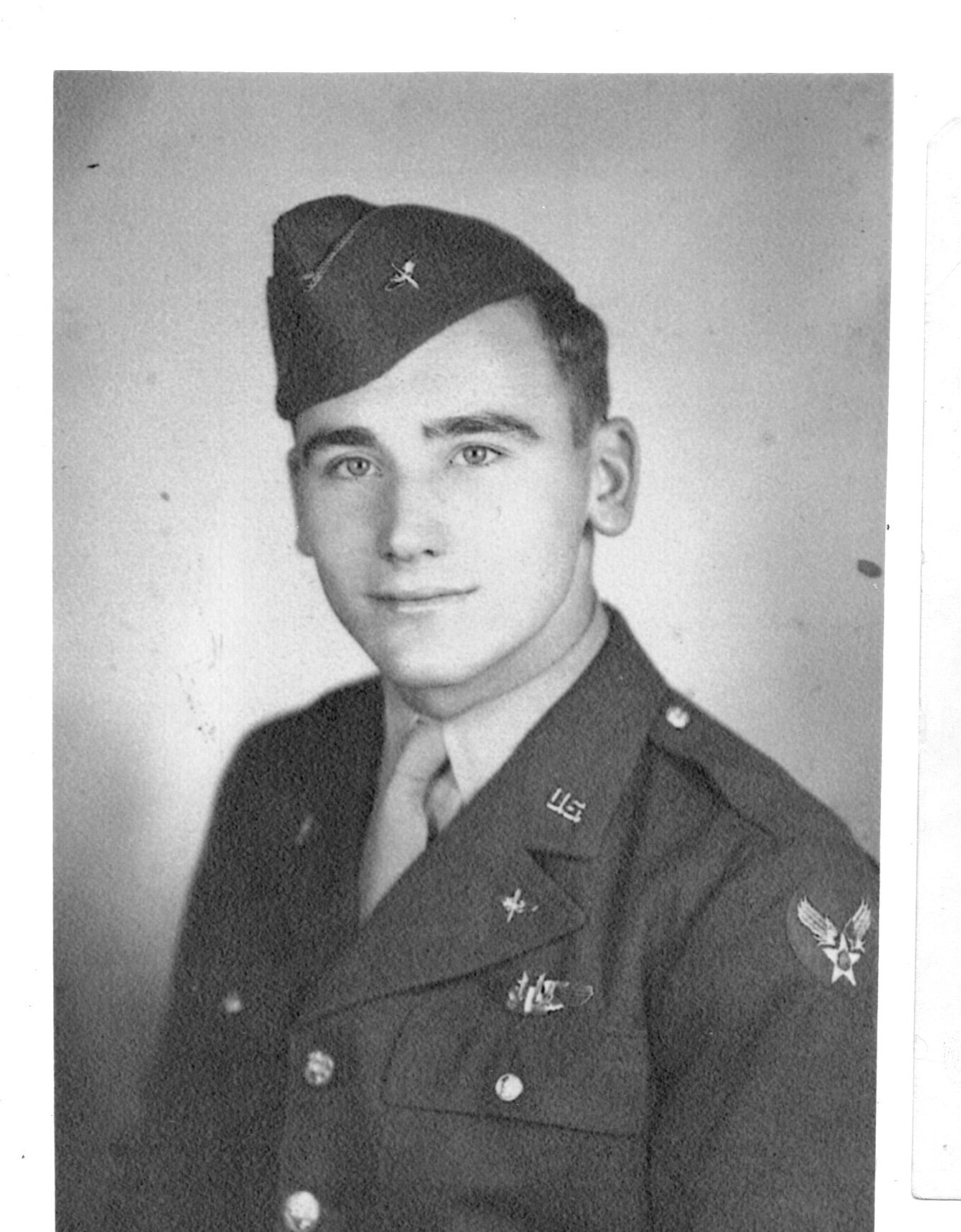

Staff Sgt. Leeland T. Engelhorn - Ball Turret Gunner

He was Teacher of the Year in 1972, raised six children (4 boys, 2 girls), had an older sister and two brothers (both fighter pilots who also fought in WWII), and he was the Ball Turret Gunner of the “Sugar Baby” B24 crew. Typically the Ball Turret Gunner was the smallest member of a crew, but not so with Staff Sgt. Leeland T. Engelhorn who at 5’11” and 180 pounds could barely squeeze into the turret. Not being the smallest and trained as a radio operator, just how did he end up the Ball Turret Gunner?

The “Sugar Baby” crew ended up with two trained radiomen, Leeland Engelhorn and John Cooper. But they needed a Ball Turret Gunner so a coin was tossed, Engelhorn lost, making him the gunner that had to squeeze into the turret. It was a scary proposition in the beginning, and he described how often he had to lie in a fetal position for 6-8 hours as being like stuffed into a tin can.

This is just a thumb-nail sketch of Staff Sgt. Leeland T. Engelhorn. We learned part of his story from an interview he gave to the Library of Congress Veterans History Project before his death (2003); other biographical information comes from phone interviews with his sons: Sheldon, Brian, Brad and Tommy. Engelhorn described himself as a child of the depression, someone who would have likely stayed in his hometown of Churches Ferry, ND were it not for the war. Once overseas, he felt culture shock. He described his crew as tightknit – a group who worked well together, something important when lives are at stake but something not all crews could manage – working in harmony. Socializing a lot together, the crew members had long discussions and there was no dissension among the regular crew. He described their time in the air as serious, and he said he lost all fear when airborne. He adds that he became hardened to his job, because it was to destroy the enemy.

Leeland Engelhorn is seated 2nd on the left.

Unlike Robert Kurtz and a few others, when he parachuted from the plane as it was crashing, he landed high in the Alps and was able to avert capture by the Germans for sixteen days. He explained that all the airmen were given escape maps, and he used his to try to plot a course for Switzerland. It took him three days to descend from the mountains and then another thirteen days moving through small villages where he stole potatoes and orchard fruit as he went into survivor mode. Eventually, after losing a shoe, practically starving for over two weeks, and looking rather disheveled, he knocked on the door of an elderly couple’s farmhouse, effectively turning himself in. The police were called and eventually he landed at Stalag Luft IV – not Stalag Luft III where Robert Kurtz and three other crew members were imprisoned. He described being a POW as traumatic and commented that Americans take for granted our freedoms until you become imprisoned. He said the conditions were harsh and sustained. The prisoners fought starvation and malnourishment, lice and other insect infestations, and were given very few amenities (they received no sheets, one thin blanket, and a mattress made with wood chips). Having lost all control over his life, as well as his dignity, he said he didn’t know anyone who was introduced to life in a POW camp who didn’t have some long-term effects.

When Engelhorn and the other 10,000+ POW’s were evacuated by the Germans and marched across Poland and Germany, he and three others made a pact to look out for each other. They traveled together, split everything they found to eat, and often carryied one injured man of the group. With very little food, he and his friends marched 500 miles over 82 days in snow and freezing temperatures. In spite of the many hardships he endured, Leeland Engelhorn called his time in the service a “great adventure.” After he was liberated (he got to shake Gen. Dwight Eisenhower’s hand overseas), he ended up at Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring’s private air field. Engelhorn and a few of his friends who had been held at Stalag Luft III “liberated” a sedan from the motor pool. When stopped by the MP’s they exclaimed, “hey we were just liberated from a POW camp and we want to drive to Paris to celebrate.”

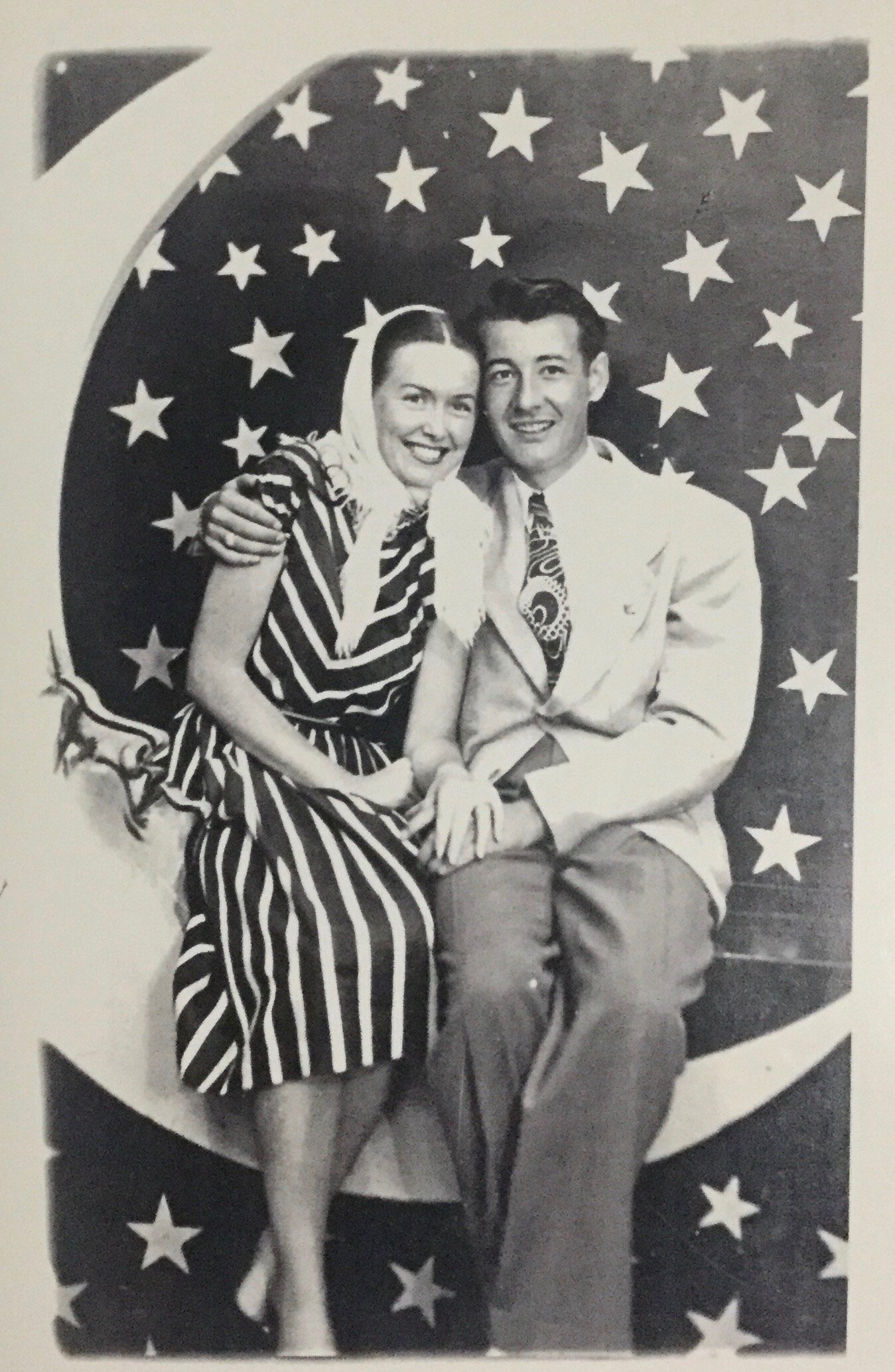

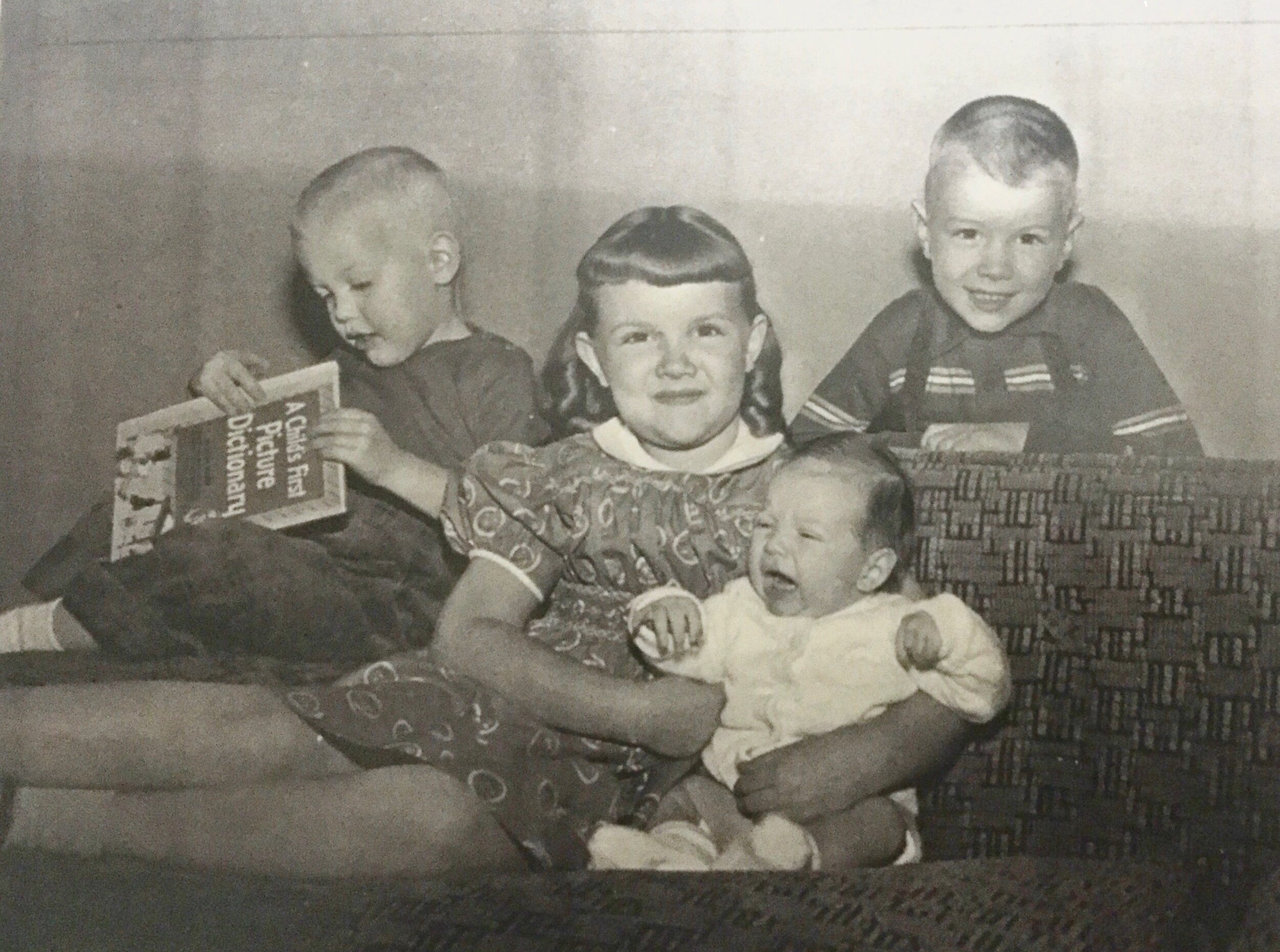

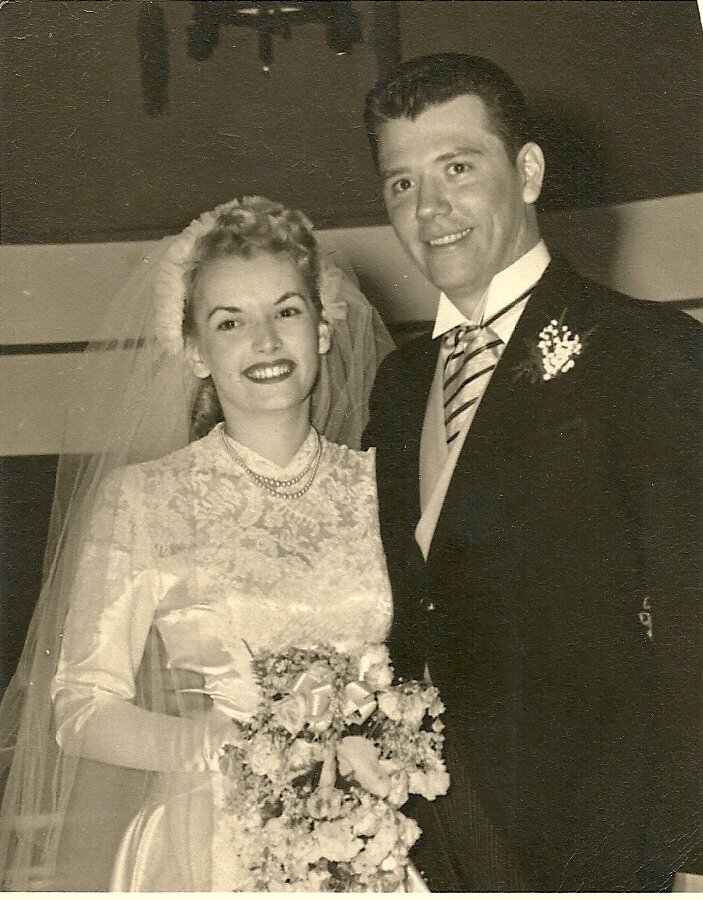

A few years after the war, Engelhorn married Ruth Eleanor Maw and over the years they had six children and lived in Minnesota and California. Engelhorn didn’t keep the equivalent of a green box in the attic, but he did bring home some mementos of his service. One, his eldest son remembers, was a giant Nazi flag, stolen after his liberation, something his kids played with. Engelhorn kept his Sergeant stripes and Purple Heart, but he also brought back a German Colonel’s winter hat, which he wore in Minnesota when his family lived there.

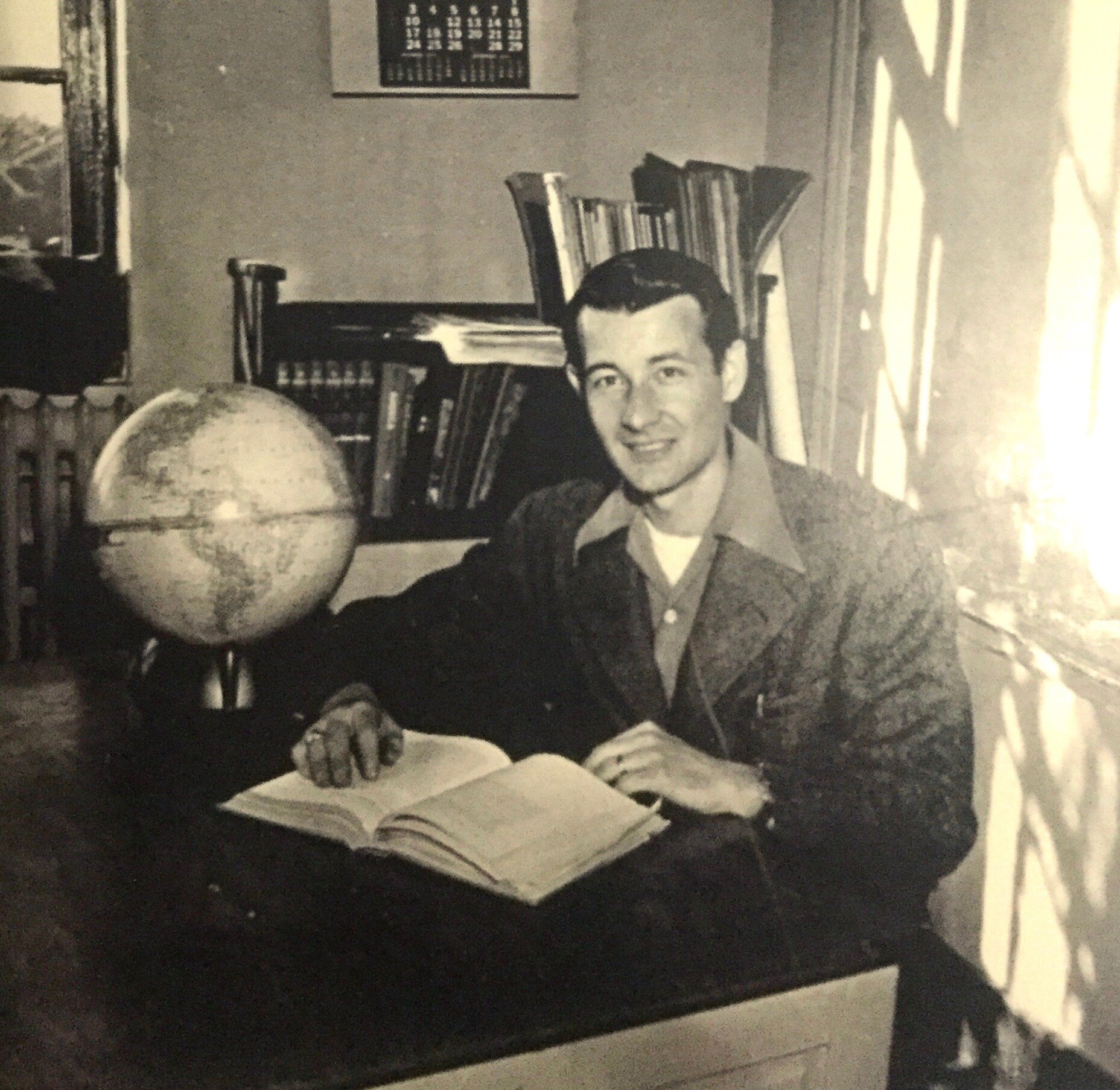

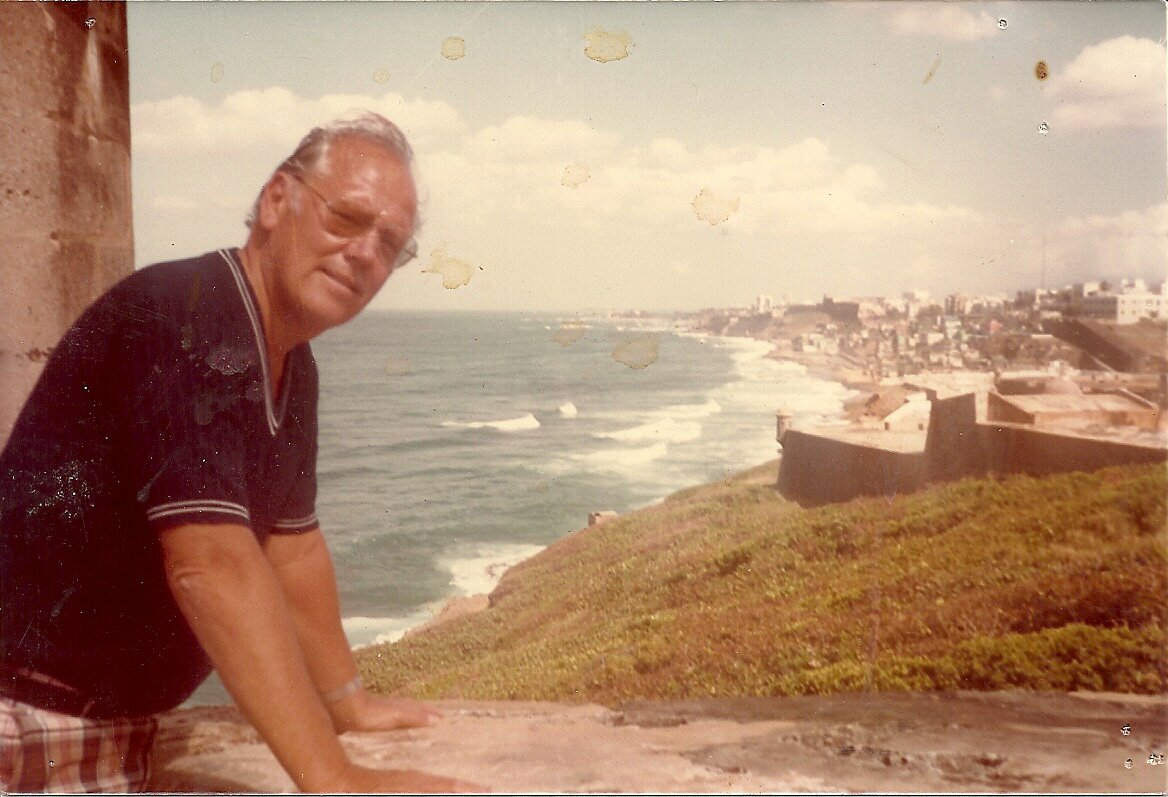

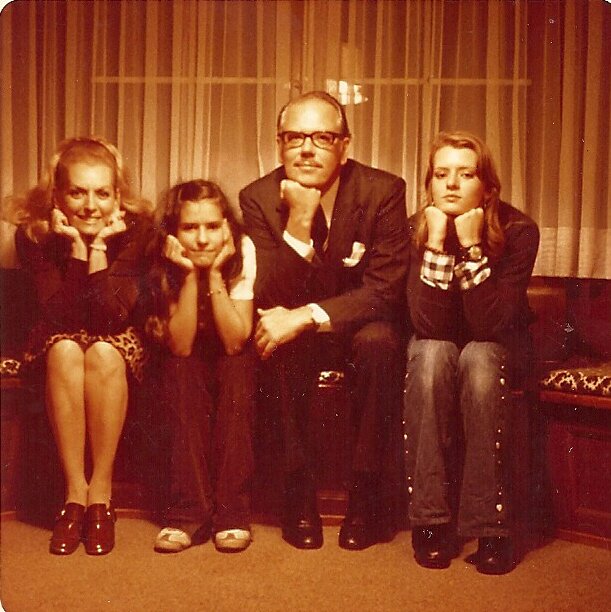

When his eldest son Sheldon was in middle school, his dad and a friend built a trailer and the family drove cross-country from MN to CA where his mother was originally from (North Hollywood). After a year, Engelhorn moved the family to San Diego where he became a founding member of Grossmont Community College. A teacher of Geography and Meteorology, he was passionate about academics. His son Tommy Lee said people instantly liked his dad; he was confidant, easy to talk to and a good storyteller. His son Brian described him as a great mentor who was patient and very well schooled. Described as someone who never got excited or raised his voice, Engelhorn was always kind and friendly. Brian and Sheldon say that while he did not have a temper, if one of them misbehaved and had to be disciplined, they preferred their mother’s switch to their dad’s “talks.” His disappointment was more painful to bear. In addition, Sheldon described his father as having absolute honesty and Tommy added that he never held a grudge.

Leeland Engelhorn experienced PTSD back home with night terrors, and days where he asked his wife to leave him alone on the sofa. He often remarked that his wife “saved him,” and his son Brad described their union this way, “Mother was dad’s beloved bride, and dad was mother’s strength.” As Engelhorn aged and began connecting with POW groups, he found an outlet to talk about a shared experience that he couldn’t discuss with his family. As the years went by, he reconnected with some of his war buddies and even returned to Ehrwald, Austria where the “Sugar Baby” was shot down with a few of his sons. His son Brad says his dad “was an incredible guy, and I miss him every day.” If you’d like to hear more about Leeland Engelhorn’s combat experience, in his words, click on this link from the Veterans History Project (video parts 1 and 2): http://memory.loc.gov/diglib/vhp/story/loc.natlib.afc2001001.00034/

Crew Member - Joseph Spontak - Navigator

In the academy award nominated film, SAVING PRIVATE RYAN, the story revolves around pulling a soldier out of combat after his family had lost three of their four sons on the battlefield (in real life the premise is based on the Niland family of NY). In our documentary, which retells the fate of the B24 “Sugar Baby” and Co-Pilot Robert Kurtz’s service, fellow airman Joseph Spontak was one of five sons in the Spontak family who served his country in WWII. Joseph (Joe) was one of seven sons and one daughter born to John and Barbara Spontak, Russian immigrants who settled in the coal mining town of Pottsville, PA in 1904.

In high school, Joe Spontak was an accomplished athlete playing both offense and defense on the football field. A 6’ tall 215 pound heavyweight wrestler, he also ran track for his high school. At 18, he joined the Air Force and after training reached the rank of 2nd Lt., and was navigator for “Sugar Baby,” flying 22 missions before the plane was shot down over the Austrian Alps in 1944. When the B24 began to freefall from 24,000’ and Spontak saw the right engine on fire, he parachuted from the plane at about 19,000’ over the mountains. He counted seconds, then pulled his ripcord only to have it fail. Continuing to plummet rapidly, he tried again. As the ripcord whipped by, smacking his mouth, it chipped several of his teeth. But that was of little consequence given what lay ahead for him.

He was captured and taken POW to the infamous Stalag Luft III, the camp where months earlier 76 prisoners had escaped via the tunnel named Harry. While three of the 76 made it to safety, Hitler ordered shot 50 of the the remaining escapees who were recaptured. Stalag Luft III would be a tense camp to land in after these events. Like many POW camps in the European theater, this one had little food, improper heating or clothing against the bitter cold winter ahead, and prisoners faced disease, depression, and parasites (Joe described lice that crawled on your eyelids and lashes while you were sleeping). But he made life-long connections with other prisoners. And he used his time there to create a ditto machine using gelatin that came in Red Cross care packages; he also used it to make maps! In spite of the discovery of the tunnel named Harry, used during the “great escape,” the prisoners were digging another tunnel - dubbed George - that went undetected. Joe Spontak acted as security detail, sitting by a window and putting a pipe in his mouth as a signal when guards were approaching.

Joe was among the tens of thousands of POWs marched across Germany in blizzard conditions in January of 1945. Hitler evacuated the prisoners as Russian troops were approaching the camps. He didn’t want the prisoners to be liberated by the Russians and used in combat against his army. Most of the men, like Spontak were a mere shadow of themselves after spending months and years in the POW camps. Spontak went from weighing 215 pounds to a mere 140 pounds. But he was resourceful, strong-headed (his daughter confided to me), and determined to live through the march.

He returned home in 1945 and later married a hometown girl, Anna Mary Harding. He became an electrical engineer on the GI bill, worked for Westinghouse and was involved in space flights at Cape Canaveral in conjunction with NASA, and raised two girls. His daughter Jane Donovan describes him as a high flyer - driven, and headstrong. But he didn’t come out of the combat zone unscathed. He had night terrors the rest of his life – terrors that became worse as he grew into his 70’s and 80’s, especially after he lost his wife. He collected stamps, coins, and ornate paper weights. And he read voraciously about WWII. Upon his death, Jane recalls there were 18 boxes of WWII books, many obscure books which she struggled to find a home for.

He never sought treatment for his PTSD until he discovered the VA medical services available to him.. That’s when he joined some groups of men sharing their war stories and resulting trauma. And while he didn’t talk a lot about much of what happened in combat, in his last days he told Jane “a part of me died that day; war is bad.” In Steven Speilberg’s movie SAVING PRIVATE RYAN based on the Niland family’s tragic history, Matt Damon (Private Ryan) makes it home alive – one of the four boys serving from his family. Fortunately, for Joe Spontak’s family, all of the five boys who served returned home after serving their country.

CREW MEMBER GEORGE HENRY BRITTON - Bombardier

Airman George Henry Britton

When he was 18 years old, George Henry Britton enlisted in the military at the height of WWII. He trained in Texas and Wyoming, and was deployed overseas as a bombardier on the B24 christened “Sugar Baby.” It was his job to take control of the aircraft via autopilot during the bombing phase of a mission. He had to sight in on his target and release tons of bombs with accuracy. This meant he had to ignore enemy fighters, heavy flak, and the very real possibility of personal injury - at 19 years old, a tremendous responsibility. George did his job expertly on his 19th mission flown on the day “Sugar Baby” was shot down: August 3rd 1944. After successfully bombing a factory in Friedrichshafen, Germany, his plane was engaged in a deadly air battle with German fighters. On the return journey, his box formation of planes headed back with the other groups in the squadron, to their base in Italy. But on the way, several of the planes were hit by flak. Although there’s a cardinal rule amongst airmen never to “break the box formation,” this group of bombers hung back with the damaged planes. At this point, U.S. fighter support, P51 -Mustangs flown by the Tuskegee airmen trained to stay with the formation, continued on, protecting the other B24’s returning to base. As the damaged B24’s and “Sugar Baby’s” group became separated from the other planes, the German fighters had time to mount an attack. Over the small village of Ehrwald, Austria, within thirty seconds, eight B24’s and eight German fighters crashed into the Alps. George Britton parachuted from the plane along with eight of his crew’s members. He was captured and taken prisoner.

Gratefully, George made it home when the war ended, returning to the Bronx where his parents lived. After the war he graduated from Columbia University with a Business degree and a diploma signed by Dwight D. Eisenhower, who later became our 34th U.S. President. In 1950, he saw Doris, a young teen who lived on his home street in the Bronx. He asked her best friend to set him up on a blind date. The day of the date, George threw his back out, and she met him while he was lying on a couch, unable to move. Despite this inauspicious beginning, and although he was six years older than Doris, he fell in love with her; they were married February of 1950.

George’s life remained adventurous; he spent a career working for Colgate Palmolive traveling the globe and raising a family. He lived and worked in Paris, London, Switzerland and Vienna and raised two girls, Lorraine (born in Paris) and Leslie (born in New York). He passed away in 2012, but his wife Doris has fond memories of George and misses him terribly. She recently told me that he was a great talker. He was never boring, and dinner at the Britton table was always interesting with George posing interesting questions to his guests. He was very well liked, and gave 120% to whatever he “set his mind to.” According to his daughter Lorraine, family meant everything to him. George was also a great public speaker, and one of his hobbies was writing.

In 2008, he wrote a novel titled CHECKMATE! Here is the book’s introduction:

“Marianne, a flaxen hair, blue eyed beauty was the prize in a chess game that might well have changed the outcome of the Allied invasion of Normandy in June 1944. Improbable you might think, but chess is taught at all military institutes since it is a metaphor for battle strategy. Marianne was a cog in the complex plot by the OSS to change the reaction of the Nazi General to that battle for Europe that could determine the fate of western civilization. No detailed knowledge of chess is required since otherwise the story would get bogged down in chess notations. Rather the chess games are kept described in simple terms of emotions and understandable to non-chess players.”

We salute George Henry Britton, bombardier for “Sugar Baby” and thank him posthumously for his service along with the rest of the crew. Below is a brief slide show of images from George’s life after the war, including photos with his daughters Lorraine and Leslie, his wife Doris, and extended family on his 85th birthday.

CREW MEMBER ANTHONY JEZOWSKI - Top Turret Gunner & Assistant Engineer

We asked Tony Jezowski’s daughter Debra Beson to tell us about her father who will be featured in THE GREEN BOX: AT THE HEART OF A PURPLE HEART. Here’s what Debbie had to say:

Anthony J. Jezowski born February 17, 1921 entered the Air Force October 26, 1942 at 21. At the time, he was living in the Detroit area and working at the Hudson Motor Car Co. He was excited to defend our country and join the Air Force. He trained at Kessler Field in Biloxi, MS, McCook Air Force Base and went to the Aerial Gunnery School in Harlingen, TX. At the base in Pantenella, Italy in August 1944, he was on a 3 day R&R and was excited to go Paris with his buddies Charlie Sellars and Larry Hamilton. But they were too late to catch the plane, it had already left! As they walked back to base, Sellars and Hamilton decided to volunteer for a mission so they could get their missions done and get home. Dad told them "No way! I am going back and resting!" That evening, as they came into the barracks to get Hamilton and Sellars, they found Dad there and told him that they needed his position: gunner, tech sergeant. He said "NO, I'm on R&R." But they kept pleading with him because 3 men had been in a car accident from another crew. Finally Dad said "I'll make you a deal, if you can't find anybody else, come back and I'll go." Of course, maybe an hour or two later they came back. Well that's the beginning of that fateful day of August 3.

Tony was released from the service in Octoober of 1945. He returned home to Linwood, MI where his family was -where he had grown up. He was a mechanic at the local car dealership. He met Geraldine Bellor and was married on September 4, 1948.

Tony Jezowski and his bride Geraldine Bellor

Shortly after his honeymoon he started his own business, Tony's Trenching Service. He bought the first hydraulic backhoe in the area and the locals laughed at him. They thought the sand would destroy the hydraulic lines. Tony knew better after learning all about hydraulics on the B24 bombers. In 1962 he decided there was a need for a golf course in the area because he loved the game and opened a 9 hole course, Maple Leaf Golf Course. While he was alive, the course grew to be 27 holes and it is still our families business.

Dad didn't do too much with other Veterans, but he had met a fellow airman from Michigan while a POW at Stalug Luft IV. Dad & John Beacon had grown up only 12 miles apart and never knew each other. Then they started talking at the prison camp and found out how close they lived to each other. They did stay in touch a little and we had the opportunity to meet John and an article was written in our local paper about the 2 of them.

Anthony J. Jezowski (Tony) was Gunner & Tech Sargeant on Sugar Baby the day it crashed in the Alps. He survived and after time as a POW returned home.

Top Row 2nd from Left: Charlie Sellars; 3rd from Left Lawrence Hamilton; 2nd from Right Tony Jezowski. These three men formed the volunteer replacement crew for “Sugar Baby.” All others perished days later

Dad was very proud to have defended our country. He always talked about how joining the air force had taught him so much. He would always say "If you don't know how it works, then you can not fix it!" and "Knowledge is Power" both learned from the Air Force. Plus he would say "You can search the world for the bluebird, only to find it in your own back yard" and a few others that he learned from books that he read while a prisoner of war. My father only had an 8th grade education, but the knowledge he had gotten from the Air Force and self taught from all his reading was amazing. Tony was a great business man and a great Father.

Tony with wife Geraldine and his sisters Mary (95) & Jeanette (91). While Tony has passed, all 3 women are still alive.